Digging the Right Grave

and the Law of Proximity

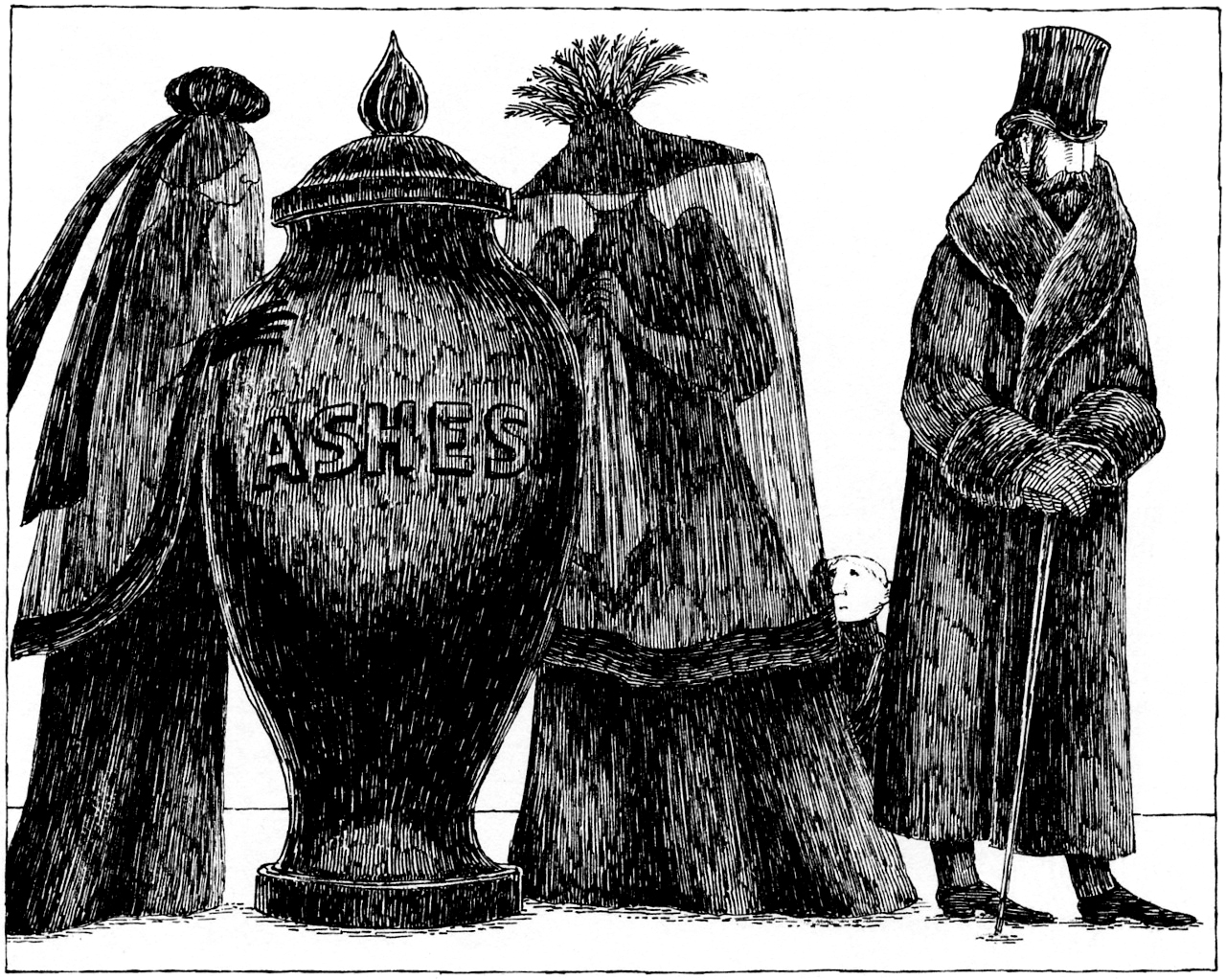

Edward Gorey, Ashes in Urn (not dated but somewhere between 1925 and 2000)

Elements that are close to each other are considered a unit. A free standing element is excluded. Something or someone who stands alone stands out.

The situation in Ashes in Urn by Edward Gorey is clear. The mourning ladies and the urn form a whole, the man stands alone. The eye is drawn to him. The rejection he experiences becomes almost palpable.

With the law of proximity ratio is key. If elements are too close to each other, a visual search slows down because it then becomes difficult to distinguish the individual pieces. They become a whole and that whole might become a mess.

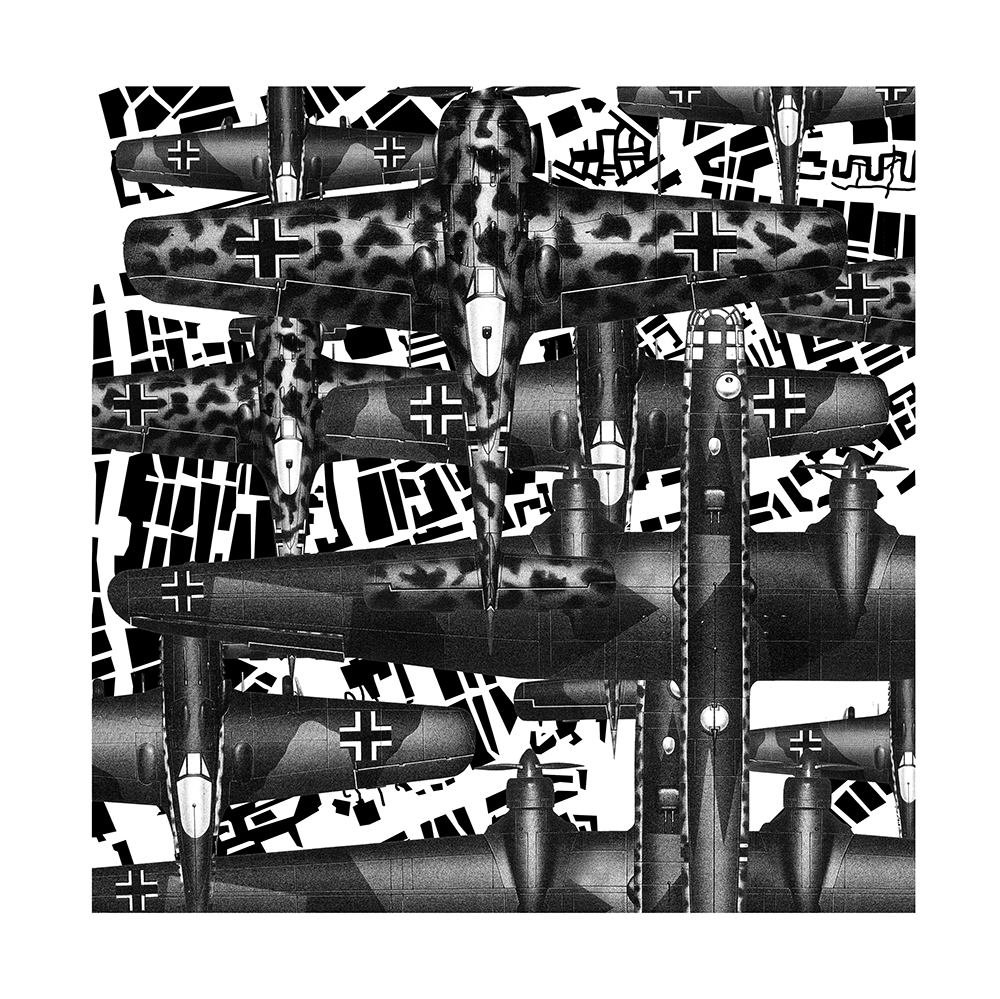

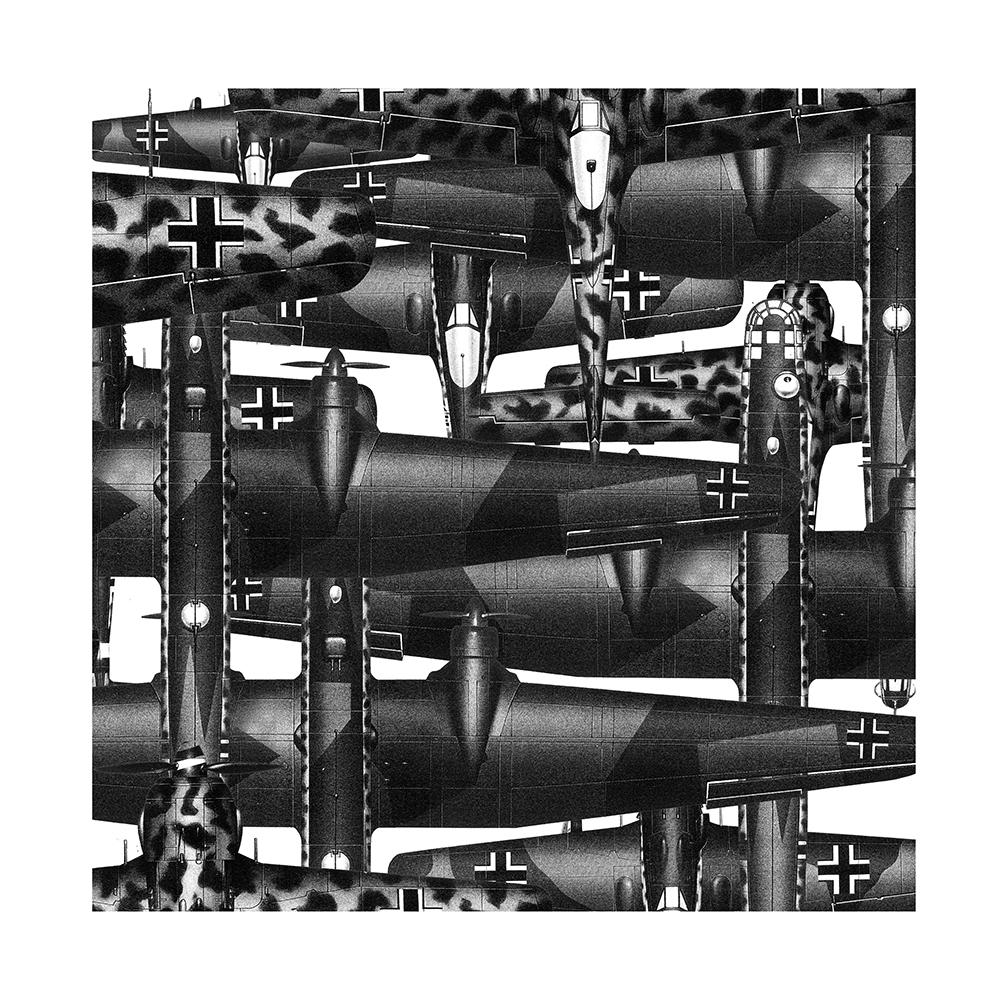

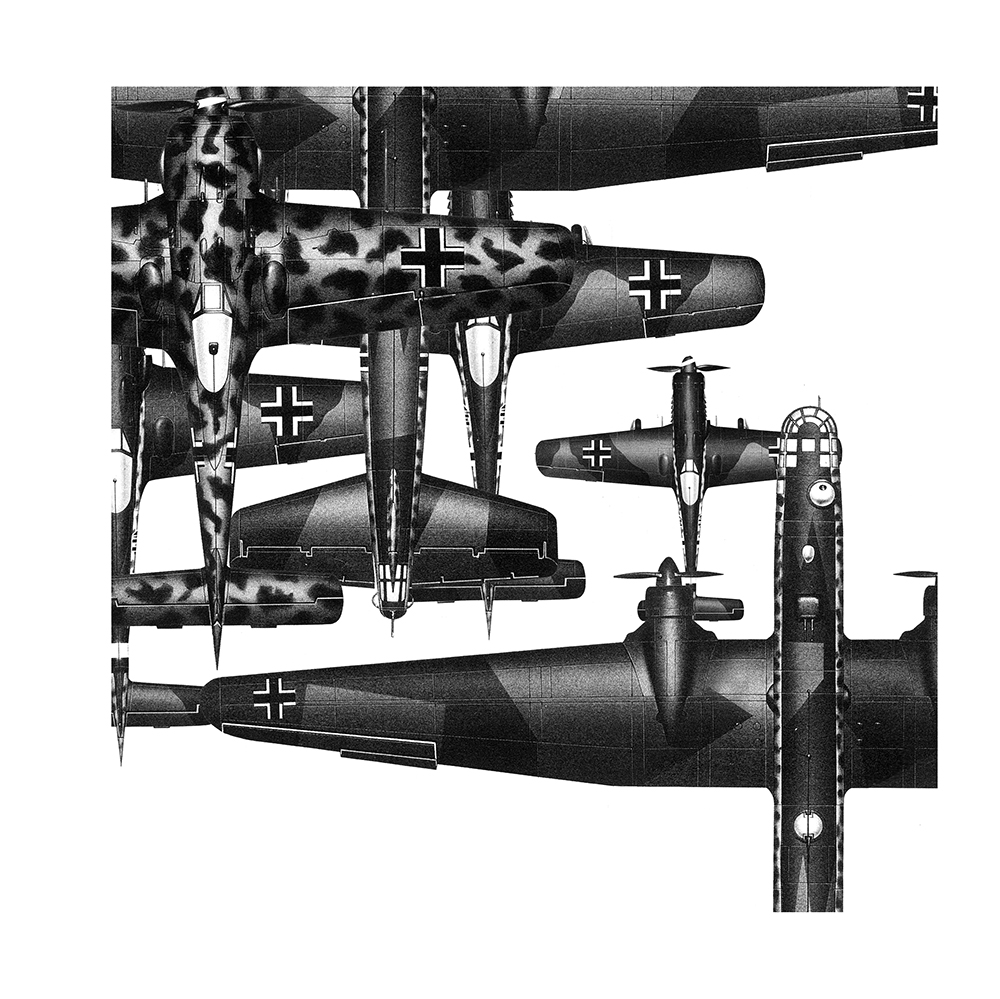

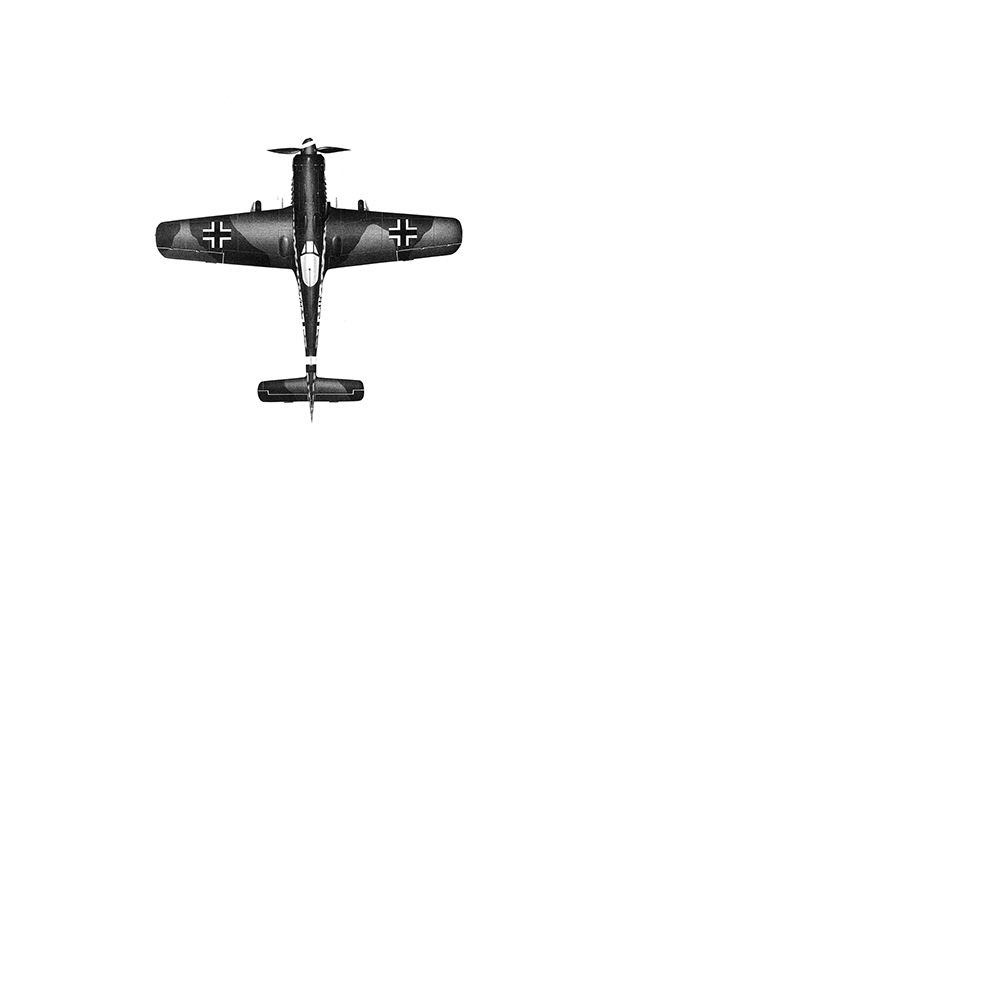

Sometimes, though, that might be exactly what you want. In the next example plains become an all-encompassing raid that, after settling down leaves the city gone.

Gemma Plum, Rotterdam Air Raid (2010). Screenprint – 8 frames from a 30 frame story

If pieces are to far apart they cease to be a whole, which, again might be excactly what you want.

How we precieve the whole and it’s pieces is not only depending on the size of the elements other in relation to the space between them. The relation to the frame influences how we experience the scene.

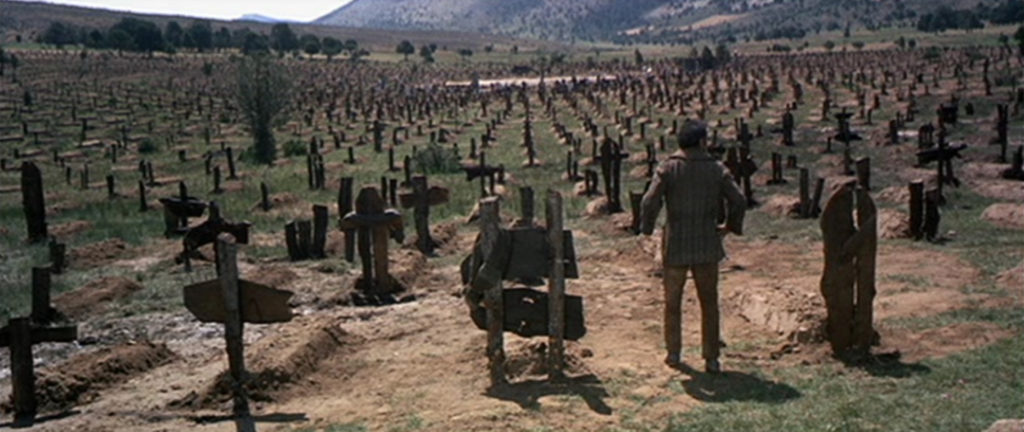

In The Good, The Bad & The Ugly (US Link) this principle is used. They have to find a specific grave in a graveyard. The enormity of the task becomes clear when a wide shot of the graveyard as a whole is shown. It is a overwhelming task, no way one grave can be singled out. To find the right grave we have to zoom in and be able to distinguish on grave from another.

Of course we could look at the graves one by one. That would illustrate the predicament but that would take a long time and make a tedious narrative. In stead Sergio Leone has the camera follow the Ugly while he runs franticly across the graveyard. Always few graves visible at the same time, blurring together remaining the whole; the graveyard and not the grave he needs. Only when the one grave is found Sergio Leone stops presenting the graves as a group, a whole. The grave is found, the puzzle is solved. It stops being a dilemma and the grave becomes a (w)hole to dig.

Sergio Leone, The Good, the Bad & the Ugly (1966)

When you’re not looking for the right grave marked by a specific name but are looking for something by comparison it is necessary to be able to look at a few elements at the same time. The distance between them and their relationship to our point of view or the frame must be just right to be able to compare them. They must be close enough to the viewer and to each other to see the relationship, but far enough from each other not to blur together. The brilliant and still very relevant movie 12 Angry Men (1957) (US Link) by Sidney Lumet provides a perfect setting for this principle.

Sidney Lumet, 12 Angry Men (1957)

12 jury members in one room trying to decide if a convict is guilty or if there is reasonable doubt. Completely different people with completely different incentives and impulses. Individuals opposing each other, finding each other, forming groups or standing alone.

It starts out with them as a whole, the jury. But immediately small differences in character are clear. Some look at the convict. Either with pity or anger in their eyes. Seeing him as a person or as a fault. Some seem to take their duty serious, some seem to be bored.

In the jury room one man starts seeding doubt. He is opposed by the group, but one by one they are convinced there is reason for doubt. Even though they are all presented with the same facts they reason differently. A twitch, a gaze a posture giving away doubt or hidden motives. The framing making it possible to compare and understand the differences.

At first he stands alone. Literally. Then he finds support. He works hard convincing the other jury members that there is reasonable doubt and bias (in any form) should not cloud judgement. One by one until even the last one breaks.

One man stands alone voting not-guilty. He stands alone facing the rest of the jury members as the group who voted ‘guilty’.

Two of the jury members vote not-guilty opposing the other jury members. Discussion begins. The group falls apart. They have to face each individual, driven by his own particular bias.

To illustrate the group dynamics Sidney Lument uses several Gestalt laws. In the stills here the law of similarity or equality and the law of equal destination are also put to terrific use. Who stands alone and how the other jury members are relating to the argument is obvious from their staging or blocking (the precise placement of characters on stage or in the frame).

Using these laws or methods in your compositions can be very powerful, especially when used to show human interaction. The posture or facial expression of listeners or onlookers can be used to enforce meaning, giving a dialogue or action (extra) context and depth.

The law of similarity or equality at work enforcing the conflict showing clearly who is opposing who and how the dynamics in the group have changed.

The law of proximity and the law of equal destination combined. Each individual distances himself from the arguments of the speaker. Illustrating that the hate this jury member feels is a personal matter and not something to consider while judging the case.

One man left. The conflict heightes by a combined use of the law of proximity and the law of equal destination.

The last man stands alone. (Combined use of the law of proximity and the law of equal destination.)