Details,

and that strange reoccurring unicorn dream…

In 1998, just before I graduated from the Design Academy, in Eindhoven (the Netherlands), I did my internship with Ben van Os. At the time he was the art director of Peter Greenaway. The films they made together were phenomenal, the stories shocking, the decors overwhelming in their colour and rich in detail. The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989) (US version

) is still one of my favourites.

Prospero’s Books (1991) (US version

) and The Baby Of Mâcon

(1993) (US version

) are less known but at least as impressive. The atmosphere they managed to create in those films is fantastic and spectacular.

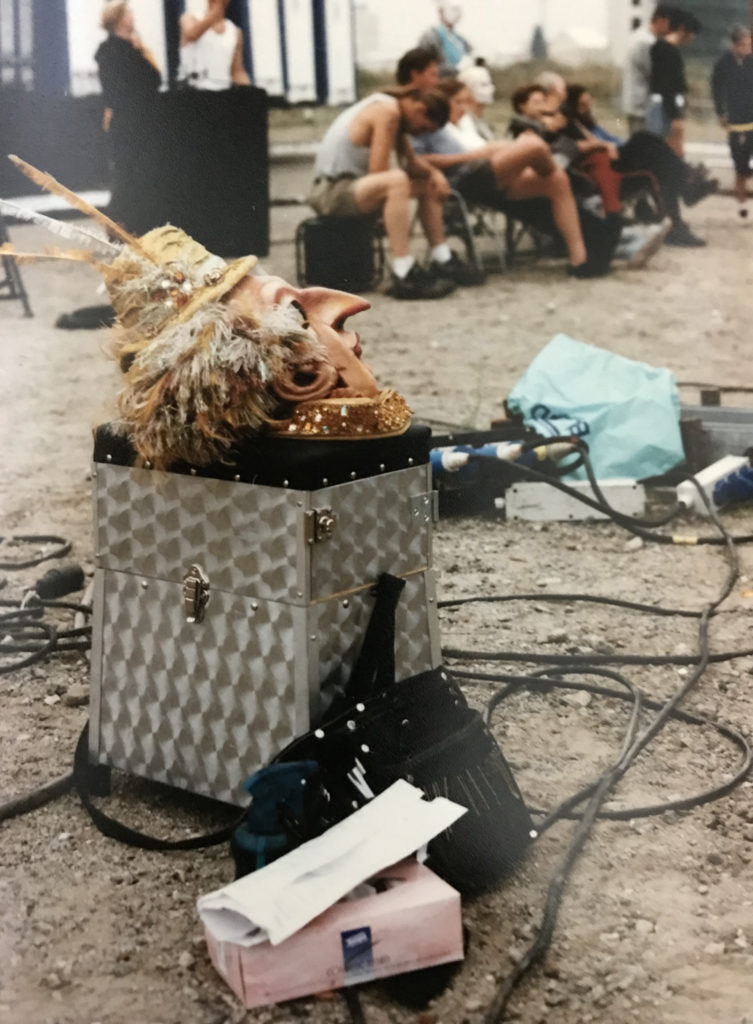

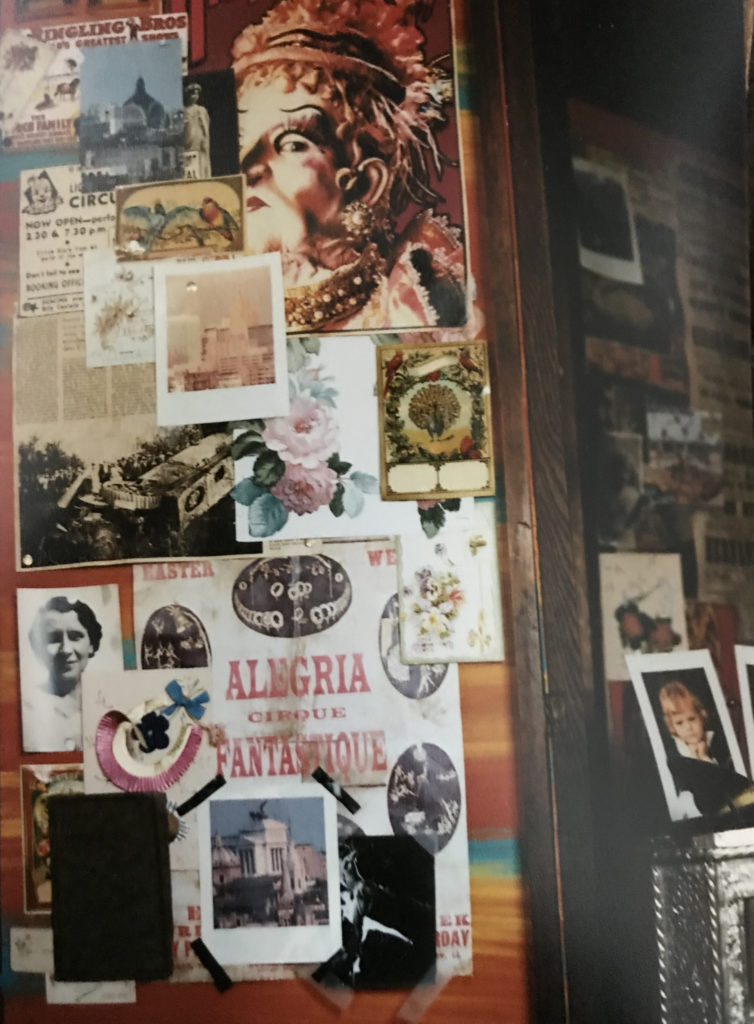

As an intern I became part of the art department for Alegria. The movie by Cirque du Soleil director Franco Dragone inspired by his Alegria show. My first task; design a caravan for a circus director (played by Frank Langella). I received the scenario and read that a monologue was planned for the fictitious circus director while he was sitting in front of his mirror. So: Caravan, Chair, Mirror. Nothing more was mentioned! I hadn’t expect that much creative freedom! I could make anything of this director; a few pictures of an old woman in beautiful frames; mummy’s boy. A few empty wine bottles and just one glass; a problematic drinker. Multiple glasses; a party beast. Make-up ordered in absurd neat rows; a neurotic. A big bulletin board with newspaper articles; a proud man from an old circus family. I could give his monolog a context that could influence the film. Of course, the impact such details make depends on the how much attention the director wishes to give them. The actor can draw attention to details by picking something up, touching it or trying to hide it, but that is not necessary. The cameraman can choose the composition and framing in a way something catches attention or goes unnoticed. Ultimately, the editor (often in consultation with the director) determines how (and if) a shot is used.

Alegria (The Movie,1998) Set

Alegria (The Movie,1998) Part of the wall of the trailer

A few years before (1992), the Director’s Cut of Blade Runner came out (filmed and first released in 1982). This Director’s Cut

(1992) was made with indirect involvement of the director Ridley Scott. Although the film flopped in 1982, it was a wonderful movie and it is now a cult classic (even more renowned since it’s resent sequel). When this Director’s Cut became success, Ridley Scott made The Final Cut

in 2007. (US versions

) That makes 7 versions in total, not counting the new 2049 one. Quite a bizarre, but different story.

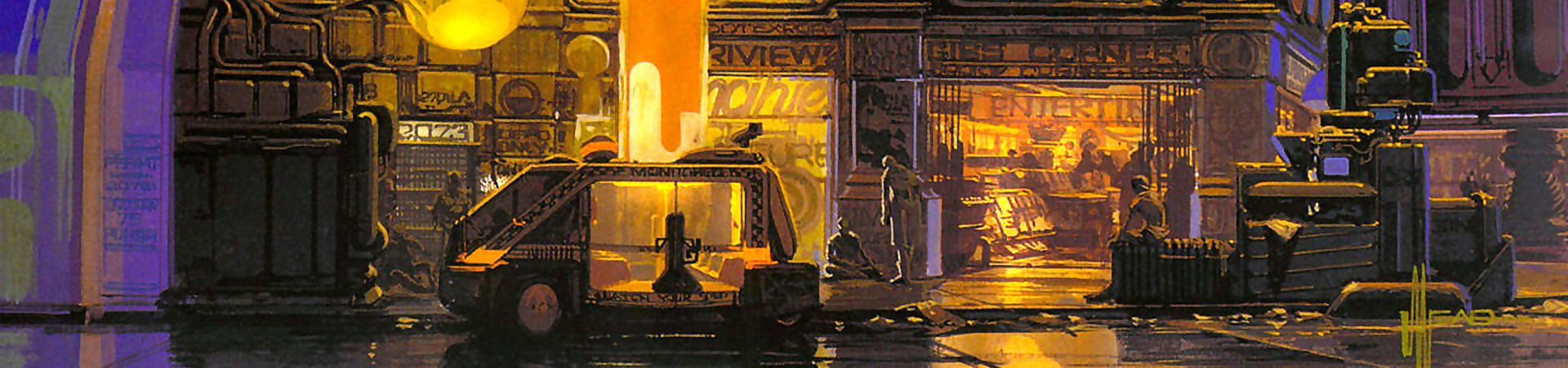

The story is situated in Los Angeles in 2019, a city in decay by pollution and overpopulation. A science fiction film with a contrasting atmosphere that clearly refers to the Film Noir from the forties. A new genre that would later be known as Tech Noir, Future Noir or Neo Noir. The Art Direction (David L. Snyder) and Production Design (Lawrence G. Paull) are impressive. In the audio comment on the Final Cut DVD, Ridley Scott says: “Most art directors are reluctant to design things in great detail, because they know the director won’t show it. But I told them, ‘If you build it, I will show it’.” Syd Mead drew the first designs based on the Métal Hurlant magazine and at the work of Moebius. (Moebius himself was first approached but declined.)

Syd Mead, desings for Blade Runner

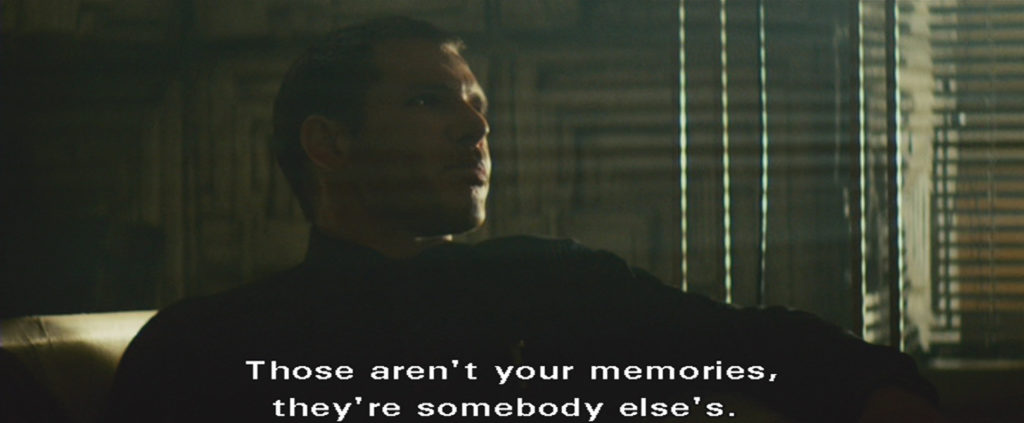

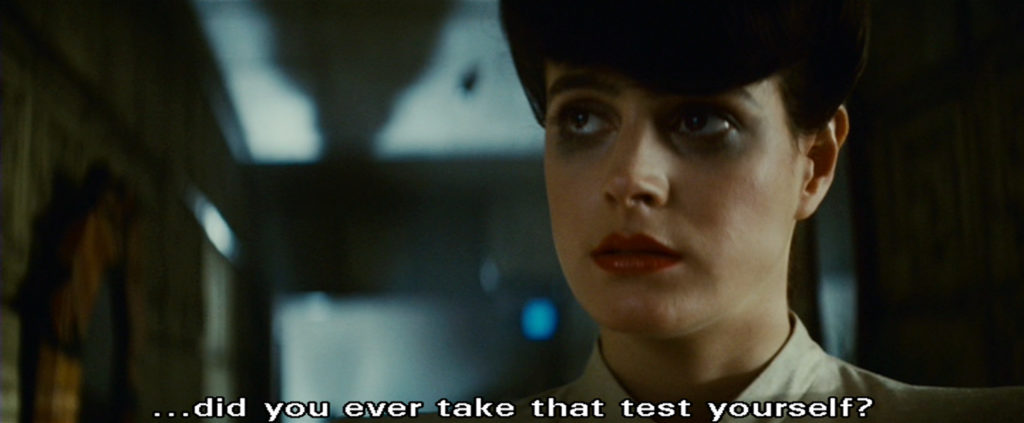

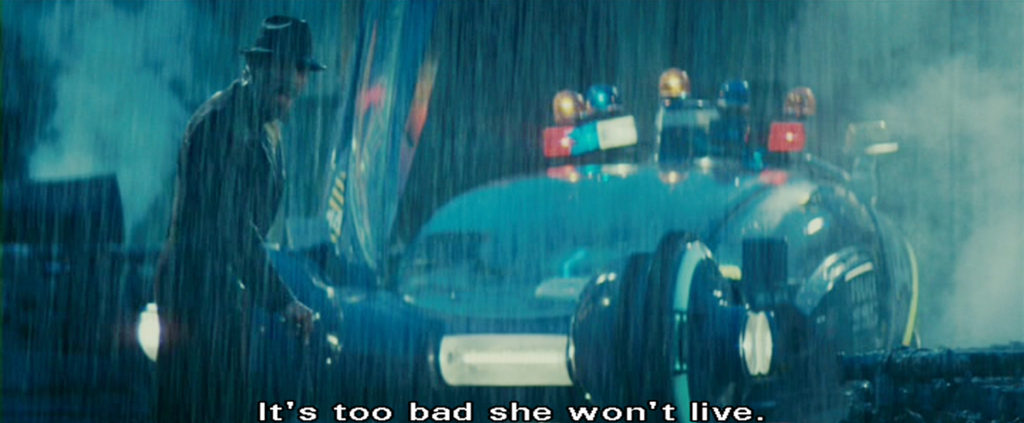

In the Director’s Cut, the story gets a completely different twist by the placement of one single detail. There were more changes; the voice disappeared, the violent scenes became longer, and the romantic end scene was deleted. But what always stuck with me was the impact that one detail could made. Stated on the back of the Director’s Cut DVD Box, “[…] a grand film still bigger. The most stimulating of everything is the new ‘unicorn’ vision, which suggests that Deckard may be a humanoid”.

Rachael asks Deckard if he has done a humanoid test on himself. A question with a double meaning; it is said humanoid have no feeling, but in this scene, he is the heartless one. It can be interpreted as her calling him insensitive. On the other hand, she asks him if he is sure he is not a humanoid himself. Since, if she is one without knowing it, he could be too. In The Director’s Cut this second interpretation of the question is hint to his true nature.

Gaff (Edward James Olmos), Deckard Colleague, asks Deckard if he is going after Rachael. He suggests that he could also escape with her. She, as Nexus 6, only has 4 years to live, but he remarks that we never know how long we have. In previous versions an existential remark, which applies to everyone. From the Director’s Cut a clue that Gaff knows that Deckard is also a humanoid.

Gaff leaves an origami unicorn at Deckards’s doorstep to let him know that his dreams are not his own, but implanted. He, therefore, is also a humanoid. Throughout the movie Gaff folds several origami figures. Without this ending, an interesting peculiarity of the character. With this ending a well-prepared plot-twist.